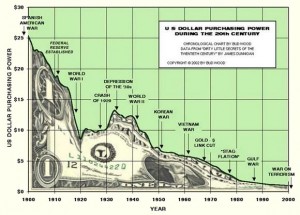

The endgame of the global financial crisis of 2008-09 has begun. The West seeks to inflate away its massive debt – by exporting inflation to the emerging East.

The endgame of the global financial crisis of 2008-09 has begun. The West seeks to inflate away its massive debt – by exporting inflation to the emerging East.

The World Bank recently warned developing countries to prepare for the risk of the world going into a slump like the global downturn in 2008-09 owing to an escalation in the eurozone debt crisis.

Ironically, the worst threat stems not from what could go wrong, but from the way the eurozone, along with the United States, seeks to resolve the debt crisis. Today, all major advanced economies – not just Japan, but also the United States and Western Europe – are sinking deeper into a liquidity trap.

Full recovery remains far away, as evidenced by the US Federal Reserve’s recent announcement that it intends to hold short-term interest rates near zero “at least through late 2014.”

In Washington, the trap was set by the exhaustion of traditional instruments of monetary policy, which prompted the Federal Reserve to initiate new rounds of quantitative easing (QE). With investors seeking higher returns, more QE has driven “hot money” (short-term portfolio flows) into high-yield emerging-market economies, inflating potentially dangerous asset bubbles in Asia, Latin America and elsewhere.

At the same time, emerging and developing countries had to move in the opposite direction of QE, that is, toward quantitative tightening. In China, interest rates were increased to 6.6 percent. In India, the central bank has raised rates a dozen times to 8.5 percent since March 2010 to bring down inflation. Brazil’s central bank recently reduced rates to 10.5 percent to shield the economy from the eurozone crisis.

In his famous 2002 speech on the potential of deflation in America, Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke suggested that former US president F.D. Roosevelt’s 40 percent devaluation of the dollar in 1933-1934 shows that the exchange rate policy can be an “effective weapon against deflation”. But because of global interdependency, domestic rate decisions in vital economies can today facilitate or constrain growth worldwide.

Already in fall 2010, Chen Deming, China’s minister of commerce, complained that “the United States’ issuance of dollars is out of control and international commodity prices are continuing to rise”. China was attacked by “imported inflation”.

In retrospect, Washington’s hot money, however, was only the first act in the ongoing crisis. The second has already begun – in Europe. Since the global crisis and the onset of the eurozone turmoil in May 2010, European leaders have tried a wide array of measures – fiscal pain, monetary easing, hollow growth, bailouts, restructurings – to contain their debt crisis, but with few results.

The remaining option: printing money.

During the past few years, financial institutions from debt-stricken eurozone countries such as Greece, Portugal and Ireland have borrowed extensively from the European Central Bank (ECB). Since May 2010, the ECB has purchased sovereign bonds from crisis-stricken eurozone member states worth 213 billion ($280 billion). This translates into increasing risks at the ECB, because of the collaterals that banks must post when they borrow money from the ECB.

In turn, the ECB has provided euro banks with massive amounts of liquidity. In December, it injected European banks with 500 billion with long loan periods of three years. The assumption is that the debt and the collaterals are sustainable.

Instead of passing the ECB money in loans to companies for employment and to stimulate the economy, banks, in turn, have re-parked the money with the ECB. As deposits at the ECB pile up, unemployment in the eurozone continues to spread.

In early January, Italy and Spain had few problems raising new funds in sovereign bond auctions. This was widely perceived as “easing of tension” in the financial markets. In turn, the ECB defended the abundant liquidity as an “effective policy measure”. In reality, the ECB was allowing some banks to use its liquidity in the auctions to buy the bonds.

What’s going on here? A cynic might call it debt monetization.

As the ECB is injecting the banks with cheap money, it is artificially creating demand for sovereign bonds. This allows the ECB to cut bank on its own bond purchases, which has been criticized, while pumping up artificial demand, which is not understood.

Naturally, euro banks love the ECB policy. Now they can borrow easy money from the ECB for three years at a low interest rate. If they use that money to buy bonds in crisis economies, they will get a much higher interest rate. Besides, they can re-park these bonds at the ECB as security, which allows them to borrow even more low-interest money. In the short term, this financial magic benefits the banks, the struggling economies and even the ECB. In the long-term, it is unsustainable.

When the money-printing machine eventually falls apart, it could severely harm the banks, bankrupt the cash-strapped countries and undermine the very legitimacy of the ECB.

To avoid Japan’s two lost decades, the West has now opted to inflate away its massive debt burden. The domestic effect is immense deflation and continued unemployment. The Fed and the ECB both are implementing vast real exchange rate depreciation by printing money. It is the West’s effort to force the emerging world to accommodate drastic inflation and thus nominal rate appreciation.

From the standpoint of the emerging East, it is comparable to successive waves of QE, which amount to debasing the value of the dollar and the euro alike. The net effect is a massive financial tsunami that has already begun to form but may eventually sweep away the emerging and developing economies alike.

The author is research director of international business at India, China and America Institute, an independent think tank in the US, and visiting fellow at Shanghai Institutes for International Studies (China).

Windows to Russia!